Decomposing Venture: Supplier Power

Global Investor Hannah Savage talks 'The Bargaining Power of LPs in VC'

Force One

Last week we covered Force One: The Threat of New Entrants: Why Everyone (Apparently) is a VC Now. This week we will continue to break down the venture capital industry with Force Two of Porter’s Five Forces.

Force Two

Second up: The Bargaining Power of Suppliers (Limited Partners).

The venture capital ecosystem is fundamentally built on the relationship between limited partners (LPs), who supply capital, and general partners (GPs), who manage it. LPs, including high-net-worth individuals, family offices, pension funds, endowments and sovereign wealth funds, provide the capital for VC funds, expecting returns from startup investments. GPs, as fund managers, make investment decisions and oversee portfolio companies. This capital supplier-manager dynamic aligns with Porter's framework, highlighting LPs as crucial suppliers. Without their capital, which VC firms primarily manage, the industry wouldn't exist, granting LPs inherent leverage in negotiations.

As we continue exploring the forces shaping the venture capital ecosystem, it's time to examine the bargaining power of limited partners, the suppliers of capital. Just as founders rely on VCs, VCs rely on LPs. Without their capital, there is no fund, no investment committee and no portfolio.

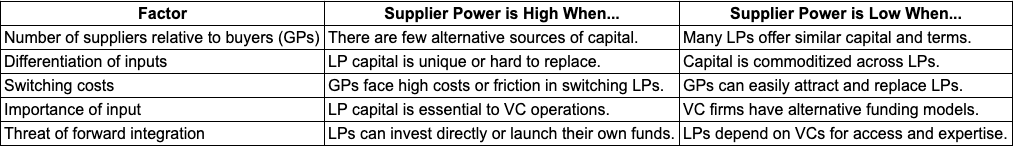

Before diving in, here’s a quick overview of what determines supplier power in any industry, applied to venture capital.

Power Dynamics

A single VC fund might have anywhere from 10 to 100 LPs, but in practice, most of the capital is concentrated among a few institutional investors. Pension funds, endowments, sovereign wealth funds and large family offices are often the cornerstone LPs of a fund, and their influence is proportional to their check size.

This concentration increases their bargaining power. If even one major LP expresses dissatisfaction or declines to re-up in the next fund, it can reshape a VC firm's entire strategy.

At the same time, the diversification of LP types, especially the growing presence of high-net-worth individuals and smaller institutions, can dilute the power of any single group. More LPs means more options for GPs, which can rebalance power dynamics.

LP Options

While LPs have always considered various investment avenues, the growth of private equity, private credit, real estate, hedge funds and digital assets has intensified the competition for their capital.

The more appealing those other options are in terms of returns, liquidity and risk profile, the more leverage LPs have when negotiating with VCs. This is a key pressure point in the ecosystem. GPs must not only compete against other funds; they’re competing against entirely different asset classes.

This is where aspiring VCs need to pay attention. It’s not enough to find great startups. You need to convince LPs that venture capital is worth the illiquidity, the volatility and the long time horizon. That means building a strategy, a thesis and a track record that stands out.

LP Dependency

Even VC firms launched by successful founders who’ve had big exits need outside capital to scale. Without LP commitments, there are no reserves for follow-on investments, no team salaries and no management fees to operate the firm. Unlike angel investors who deploy personal wealth, VCs manage other people’s money, and that comes with strings attached.

Top-performing VC firms with strong brands can often set terms. LPs may accept higher management fees or lower profit shares in exchange for access. But that power isn’t universal. Emerging managers, especially first-time fund managers, may need to offer better economics to attract capital: lower fees, higher hurdle rates or more transparency.

In some cases, LPs form Limited Partner Advisory Committees (LPACs) to collectively influence fund decisions, especially when performance is in question or conflicts of interest arise.

Economic Cycles

During peak fundraising periods like 2021, GPs could be selective, even rejecting LPs that didn’t align with their mission. But when markets cool, as they did in 2022 and 2023, and exits slow down, LPs become more cautious. They focus more on returns and terms, and their ability to walk away carries more weight.

In leaner years, GPs may find themselves with fewer options and more pressure to accommodate LP demands in order to close their fund.

Other Trends

The secondary market for VC fund stakes gives LPs more liquidity. They’re not locked into 10-year cycles the way they used to be.

Co-investing and direct investing are on the rise. LPs want more control and more upside, and in some cases, fewer intermediaries.

Emerging managers are gaining interest, offering LPs access to niche markets, diverse teams and less crowded deals. But these GPs are often at a disadvantage in negotiations.

Zombie VC firms, those unable to raise new capital or generate meaningful returns, may be more inclined to meet LP demands just to stay alive.

Big Picture

Venture capital is built on a two-sided trust dynamic. Founders trust VCs to deliver capital, support and guidance. VCs, in turn, rely on LPs to fund the entire operation. When supplier (i.e., LPs) power increases, it affects how GPs behave: how they invest, what they prioritize and how they engage with their portfolio.

For anyone looking to break into venture, manage a fund or write angel checks, understanding the role and influence of LPs is non-negotiable. They are not passive participants. They shape the ecosystem just as much as the founders and firms they invest in.

The series will continue with Force Three: The Bargaining Power of Buyers (i.e., Startups)—how founders can (and do) influence venture capital decisions.

Subscribe

Follow the “Decomposing Venture” series by Global Investor Hannah Savage using the “Subscribe now” button below.